Scrooge Season

On winter pessimism, seasonal hope, and against-the-grain Christmas stories.

A few months ago, I wrote my Notes on Autumn in the warm glow of sweater season. A few minutes after publishing that column, the fuzzy feeling sharpened and the sweetness soured as I thought about what comes next: winter.

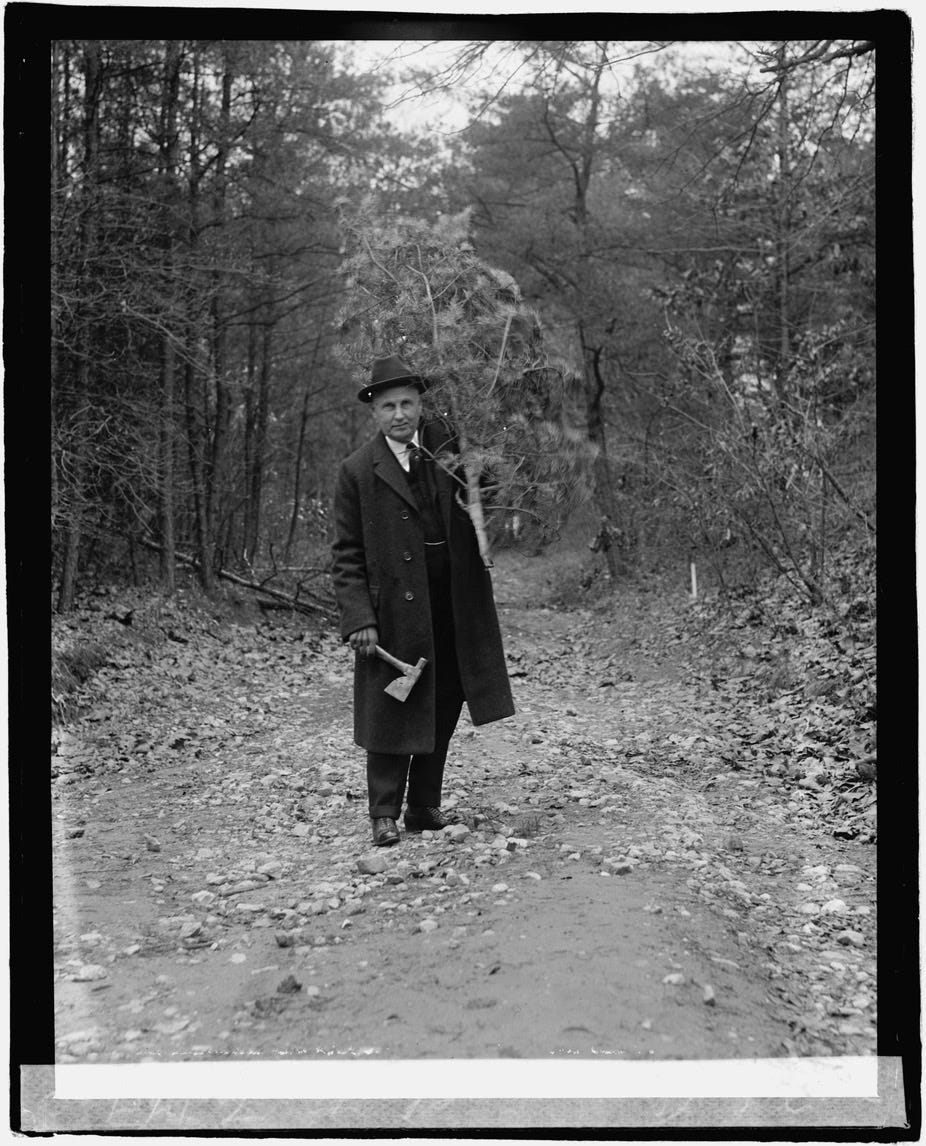

Fall might start with pumpkin-spiced everything, but it ends with pumpkin-damned-spiced every-damned-thing. The romantic flutter of falling leaves in September becomes, by December, the stark bareness of naked trees. The waning of autumn means grey daylight, the stretch of nights, and creeping cold, a slow dying that leads to death in winter.

I’d be happier with a three-season climate where autumn doesn’t succumb to winter but rolls painlessly into spring. But winter is inevitable. That might be why the literary critic Northrop Frye saw autumn as tragedy — like a tragic play, the season can’t escape its fate. The inevitability of decline is a hallmark of a good tragedy, but a defining part of watching a tragedy is that, despite knowing that things are headed for an unhappy ending, we hope against hope that things might work out somehow.

Maybe this time we can ignore Shakespeare’s opening Chorus, and Juliet will elope safely with Romeo in the end. Maybe this time the opening line of The Virgin Suicides — where the narrator tells us that all five Lisbon girls will kill themselves — will be a misdirect, and actually the sisters will be fine. Maybe this year, somehow, we won’t have a winter.

This magical thinking takes hold every autumn. For a while, the smell of wood smoke and the mulch of soggy leaves establish an atmosphere I can live with, so long as it doesn’t get any colder, any darker, if the seasonal depression stays quiet this year. Then the darkness swallows the days, and my mood grows less stable than a seesaw and as buoyant as a cannonball, but still I hope this winter will be bearable in a way no other winter ever was.

This is the tragic yearning of tragedy: for the inevitable to be preventable somehow. Philip Roth’s “blessed mysterious somehow!” The same “somehow” that allows us to live lives of inevitable mortality. We know how our story ends (it ends) but we wake, shower, drive places, read Substack, eat lunch, play at life as if we don’t know what we know, or as if it might end differently — somehow.

Unstoppable force, meet the immoveable object of my hope.

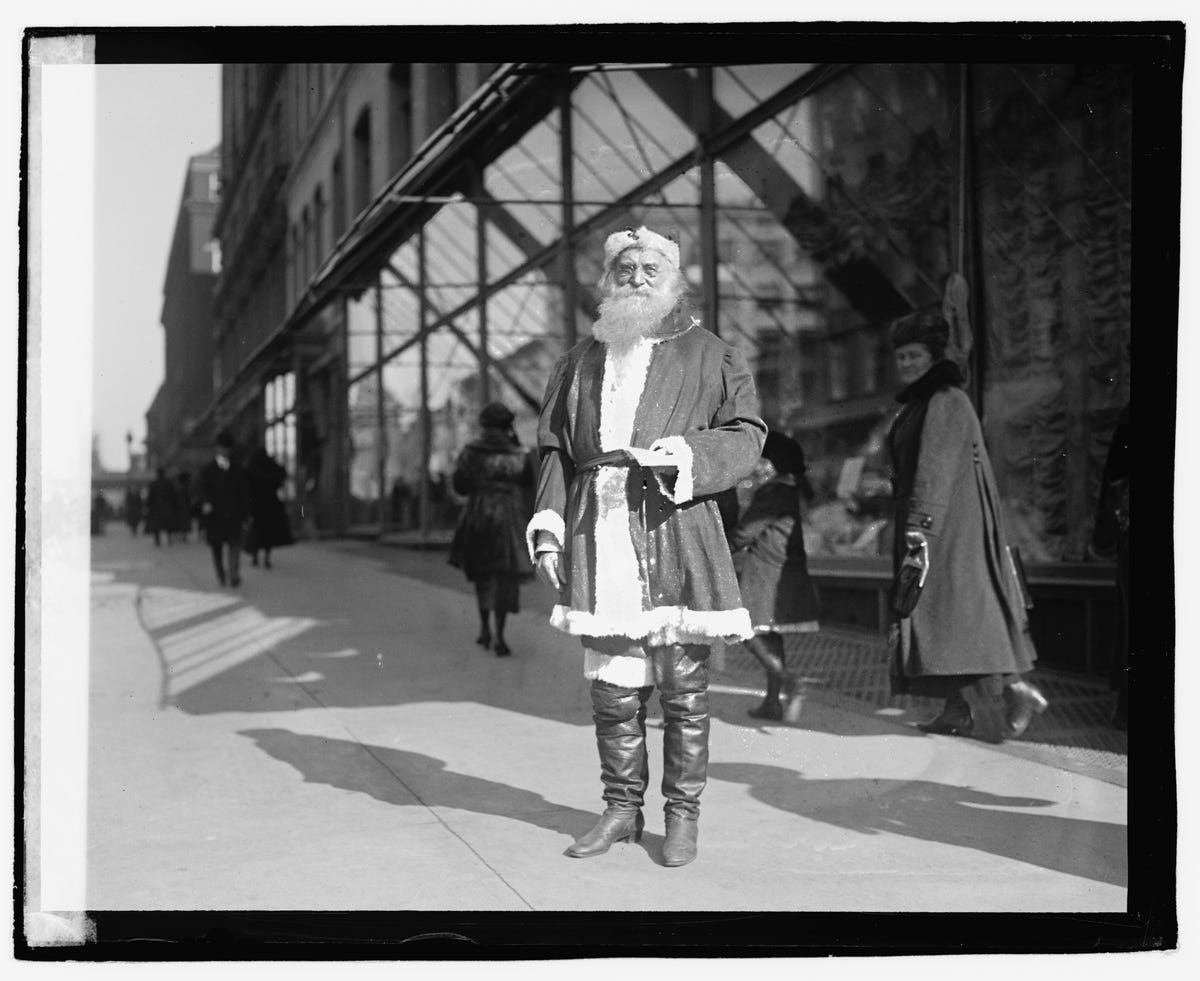

This scroogery about the season is, in my experience, best sedated with reading. Books help to resist the bah-humbug of it all. At no other time of the year is escapism more needed and less tolerant of its usual snobbish criticisms. But for some dumb reason, this year I thought I’d show that I was too savvy for Christmas cliché, for the garish sweaters and festive hold music and Coca Cola ads.

So I found an against-the-grain Christmas story that doesn’t take sentimentality as the only sentiment of the season: John Cheever’s “Christmas is a Sad Season for the Poor”, published in The New Yorker in 1949, in which Charlie, an embittered elevator operator, has to work on Christmas day. As tenants of the building ride his elevator and wish him a merry Christmas, he replies each time with:

“Christmas is a sad season if you’re poor. You see, I don’t have any family. I live alone in a furnished room.”

The repetition of this moment goes from tedious to ridiculous to a blend of both. The ridiculous is something Cheever leans into throughout the story. It’s sort of the whole point.

When the tenants perform a narratively unsurprising act of goodwill by sharing their food and gifts with Charlie, the reader isn’t invited to contemplate what so reliably moves people to kindness, but to laugh at the absurdity of Charlie’s situation. The longest paragraph of the story lists what he receives in exhaustive detail (meant to be more amusing than exhausting):

“There were goose, turkey, chicken, pheasant, grouse, and pigeon. There were trout and salmon, creamed scallops and oysters, lobster, crabmeat, whitebait, and clams. There were plum puddings, mince pies, mousses, puddles of melted ice cream, layer cakes, Torten, éclairs, and two slices of Bavarian cream.”

There’s echoes here of A Christmas Carol, especially Fezziwig’s party, where Dickens writes:

“There were more dances, and there were forfeits, and more dances, and there was cake, and there was negus, and there was a great piece of Cold Roast, and there was a great piece of Cold Boiled, and there were mince pies, and plenty of beer.”

When some partygoers start “pouring out their hearts in praise of Fezziwig”, the Ghost of Christmas Past dismisses Fezziwig’s kindness as a minor thing not worth celebrating. “He has spent but a few pounds of your mortal money,” says the ghost. “Is that so much that he deserves this praise?” Scrooge, bristling and newly righteous, insists that “the happiness he gives is quite as great as if it cost a fortune.”

Cheever, on the other hand, seems to take the spirit’s side. In his story, every act of kindness is a mere surplus of consumer spoils rendered axiologically empty by how little they cost to give away. The miserliness of Cheever’s vision is snide and didactic. You get the feeling that he didn’t have a story to tell as much as a point to make, and the point is: Don’t buy all that crap about kindness at Christmas. People are self-serving in their efforts to seem selfless.

In the penultimate line of Cheever’s tale (perhaps the best of many well styled sentences here), a woman rushes to perform some charity because “we are bound, one to another, in licentious benevolence for only a single day, and that day was nearly over”. Licentious benevolence is the kind of phrase that makes an instant home in your memory and rewards close attention. It suggests that charity might be untoward, maybe even immoral, something to snub in favour of restraint. It’s a phrase that could have come straight from Scrooge.

Having read Cheever’s story, I no longer want to be cool about Christmas. Winter and its nights are terribly long, and I have a daily low-level bad mood brought on by the dark and the cold, and I’m fighting it off with fistfuls of Vitamin D tablets and the glare of a SAD lamp, so excuse me if I don’t scoff at simple things that bring simple pleasure. I’ll take what cheer I can get, wherever I can get it.

Still, it feels embarrassingly basic to write about snow drifts and mistletoe and long walks on Christmas morning. It makes me think I should write a blistering takedown of these single entendre images passed along like urban legends no one really believes yet everyone clings to. I worry the same worries Paul Auster describes in an article for The New York Times, when he had to write about Christmas:

“I spent the next several days in despair, warring the ghosts of Dickens, O. Henry, and other masters of the Yuletide spirit. The very phrase, ‘Christmas story’, had unpleasant associations for me, evoking dreadful outpourings of hypocritical mush and treacle. Even at their best, Christmas stories were no more than wish-fulfilment dreams, fairy tales for adults, and I’d be damned if I’d ever allow myself to write something like that.”

And I hit the same wall that Auster hit next:

“And yet, how could anyone propose to write an unsentimental Christmas story? It was a contradiction in terms, an impossibility, an out-and-out conundrum.”

He has a hell of a go at writing what he deems impossible, an unsentimental Christmas story. He tells a story that wrestles with the slippery moral ambiguity of indulging a “happy lie”, an untruth that brings some joy to a deserving person. It’s about stolen cameras and a blind grandmother, but at bottom it’s about the morality and utility of Christmas stories, which might be false in some aesthetic sense but deeply true, or even good, in a humanistic sense.

I liked this story, but I’m not sure about this central idea that pitches the good and the beautiful against the true. What if the sentimentality that Auster rejects in Christmas stories isn’t actually untrue? What if the unadorned hope he dismisses as “fairy tales for adults” and the goodness he brushes off as “mush and treacle” is something truer than true?

Maybe it’s the kind of thing found, in the words of E. E. Cummings, at “the root of the root” and “the sky of the sky of a tree called life”. Maybe we return to those things, year after year, because the tree “grows higher than soul can hope or mind can hide”.

There’s a line I copied out years ago from David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest. Part of the sentence does the rounds every so often on social media. Wallace writes that “what passes for hip cynical transcendence of sentiment is really some kind of fear of being really human, since to be really human ... is probably to be unavoidably sentimental and naive and goo-prone and generally pathetic”.1

This is a challenge to the modern view of irony as the highest evolution of cultural attitude. Intellectual detachment from sentiment might just be an expression of our own deep anxieties about being human.

I don’t think it’s incidental to my reading of Cheever’s story that I’m so weary of the trendy iconoclasm of our age. I think if I’d read it when it was published in the mid-twentieth century, I’d have had a different response. Cheever’s society was saturated in saccharine sincerity, but I read it in an age that’s worn itself out with insistent irony. He and I were both reacting against our own contexts.

There’s a bit in Cheever’s story where he tells us that Charlie resents being an elevator operator and “held the narrowness of his travels against his passengers ... as if they had clipped his wings”. Later, though, he sees his vertical travel as a kind of superpower, and he giddily speeds up and down the building in his elevator. What’s changed? Well, things around his job have changed, from being fed and given gifts to feeling seen where before he’d felt invisible. The context has changed.

How an audience reacts to what they’re shown depends, to some non-negligible degree, on where and when and how they receive the thing. I might re-read Cheever’s story in summer and appreciate it better out of season, just as I once re-read A Christmas Carol in spring and saw it as a little naive and very heavy-handed.

For now, in the darkest part of the year, I want a little light. Maybe not Christmas carols and kitschy knitwear, but something warm, something kind. Even if it’s only a fairy tale for adults.

Wallace goes further, describing humanity as “forever infantile, some sort of not-quite-right-looking infant dragging itself anaclitically around the map, with big wet eyes and froggy-soft skin, huge skull, gooey drool” — not quite the uncomplicated affirmation of sincerity most people think the quote is in its abbreviated form.

Lovely stuff, Matthew. At this time of year, I like to murmur to myself some Shelley: “O Wind, /

If Winter comes, can Spring be far behind?”