Sweater Season

On Bill Bryson's New England, the ghosts of autumn past, and a hymn to the stuff you can’t measure in a test tube.

If you’re not a regular reader of Rumaan Alam’s Current Enthusiasms, you’re doing it wrong (where “it” is digital reading). I promise you’ll love the substack, unless you’re allergic to smooth writing peppered with sharp expressions of sharper observations.

A recent piece on the revival of autumn argues against the idea that the objectively measurable is the only way to experience life and “that the equinox is a more meaningful marker of time than the children going back to school”:

“Supplies appear in stores, the yellow buses are back on the road, and likely you itch to buy a new jacket or shoes or notebook. A new season, despite what the thermometer or earth’s rotation have to say about it.”

Here’s what I wrote in reply to that post (a comment that has the endorsement of the author’s “like”, which, as we all know, is shorthand for “what a brilliant observation surpassed only by the rare eloquence of its noble expression”):

“I’ve always trusted the seasonal barometer of the soul more than the calendar on the wall to tell me when autumn arrives. In our household, it’s already sweater weather, and I’m pleasantly haunted by the phantom scent of pencil shavings every time I hear the shush of a car through the puddles in the street.”

Current Enthusiasms is always short and straight to whatever point Alam is making, like he’s swept the clutter from his desk except for one small object that he hovers over with a magnifying glass. You look closely and clearly at that thing until it’s burned into your vision. That’s why I spent the rest of the day thinking about when autumn actually begins and how it announces itself.

The arrival of Autumn is a kind of call-and-response. The leaves that begin to litter the pavement sound, under boots, like crisp paper scrunched in a toddler’s fist: call. Then I return to a certain set of beloved films and books: response.

To celebrate the cosy sweater of autumn, my wife and I have an at-home week-long film festival. The line-up typically incudes It (a comfort film more than a horror movie) and Sleepy Hollow. There’s You’ve Got Mail, When Harry Met Sally, and Moonrise Kingdom. The Holdovers recently made the line-up, and this year we plan to add Good Will Hunting. If it’s set in a college, or New England, or (the holy grail) both, the lights go out and we lean into cliché with glorious abandonment of self-conscious snootiness.

Then there’s all the books. I return to Shirley Jackson, but not the obvious choices. Hill House is for Halloween; her two-part memoir (set, no surprise, in New England) is for September. There’s The Secret History by Donna Tartt, The Saturday Night Ghost Club by Craig Davidson (Toronto, but close enough), anything by Stephen King, and chapter eight of The Great Gatsby (New York, more than close enough, and set during the fall).

I also go to “Fall in New England” from Bill Bryson’s essay collection, Notes From a Big Country. Here, he describes hiking in the seemingly continental expanse of forest in his New England backyard, where he makes two discoveries.

First, Bryson finds that only the language of hyperbole is rich enough to express the grandeur of fall in Vermont:

“It is a truly astounding sight when every tree in a landscape becomes individual, when each winding back highway and plump hillside is suddenly and infinitely splashed with every sharp shade that nature can bestow — flaming scarlet, lustrous gold, throbbing vermillion, fiery orange.”

Second, he realises that it’s only hyperbole at first glance, that the product lives up to the hype:

“For one thing, the New England landscape provides a setting that no other area of North America can rival. Its sunny white churches, covered bridges, tidy farms and clustered villages are an ideal complement to the rich earthy colours of nature. Moreover, there is a variety in its trees that few other areas achieve: oaks, beeches, aspens, sumacs, four varieties of maples, and others almost beyond counting provide a contrast that dazzles the senses. Finally, and above all, there is the brief, perfect balance of its climate in fall, with crisp, chilly nights and warm, sunny days, which help to bring all the deciduous trees to a coordinated climax. So make no mistake. For a few glorious days each October, New England is unquestionably the loveliest place on Earth.”

Those sunny white churches and covered bridges make frequent appearances in my autumnal daydreams, which are coloured by the fall foliage of this distant land I’ve never been to but yearn for every September.

Something strange: most of the things that give me the autumnal warm and fuzzies don’t relate directly to my own life.

The smell of pencil shavings wafts like a ghost smell from nowhere and transports me to my favourite season — but I don’t remember the last time I sharpened a pencil. The smell is related to the school supplies in Alam’s list of seasonal markers, the pencil cases and erasers and notebooks showing up in stores. Except I don’t have a kid, and I left school more than twenty years ago (cue the vertiginous realisation of time passing, age increasing, remaining life decreasing...).

Then, there’s the yellow school buses Alam says herald the arrival of fall. Picturing them jumpstarts the synapses permanently wired to September, except I’ve never seen a yellow bus outside of a movie. They’re not used here in England, where I’ve spent most of my life, and I don’t remember seeing any in Canada, where I spent my youngest years, though I suppose I could have just forgotten. What I’m sure of is that yellow school buses are a distinctly North American thing, just like calling autumn “fall”.

Speaking of Americanisms, here’s my current wallpaper on my Macbook:

I’ve never played American football in my life. I don’t watch it on TV. I care about it as little as I care about all forms of sportsball. I was never popular enough as a kid to have the number of friends in the painting. The house looks nothing like any house I’ve lived in or that line the streets of the little city where I live. So, nothing in the painting looks anything like my life. What it does look like is autumn, as autumn looks in my head.

In “Fall in New England”, Bryson doesn’t have time for the intellectual blockheads who traipse around Vermont “with the scientific equivalent of a paint chart” and proclaim “with a grave air of discovery that the maples of Michigan or the oaks of the Ozarks achieve even deeper tints”. This is, of course, to miss the point of the experience. He describes, with the love of a local and precision of a skilled pen, what makes New England’s fall display unique.

And then the article turns, subtly, distinctly, to reveal what we’re really doing here.

Bryson tells us how “trees prepare for their long winter’s slumber by ceasing to manufacture chlorophyll, the chemical that makes their leaves green”. Now, other chemicals get to show off by “creating the yellow and gold of birches, hickories, beeches and some oaks”. For these chemicals to work, the tree must keep feeding the leaves even though they’ve ceased to be useful. Some trees expend even more energy manufacturing an additional chemical that accounts for “the spectacular oranges and scarlets that are so characteristic of New England”.

“Just at a time when a tree ought to be storing up all its energy for use the following spring, it is instead expending a great deal of effort feeding a pigment that brings joy to the hearts of simple folk like me but doesn’t do anything for the tree.”

Without this section, Bryson’s article would be well-written and diverting enough, offering a few wonderful sentences ripe for a harvest of Instagram quotes about the charms of autumn. Instead, a pretty anthem becomes a deeply thoughtful hymn to the stuff you can’t measure in a test tube. It’s a celebration of experience. If you want a ten-dollar word to lend intellectual credibility to what can seem new-agey, philosophers call this “phenomenology”.

Speaking of ten-dollar words, I sometimes think of this as moving aside the sublunary to make room for the sublime. A band called Silent Planet put it better: “I’m learning what it means to trade my certainty for awe.” Bryson shows how the academic comes along and says, We can quantify beauty, measure the seasons, put numbers on feelings, and the world says, That’s what you think.

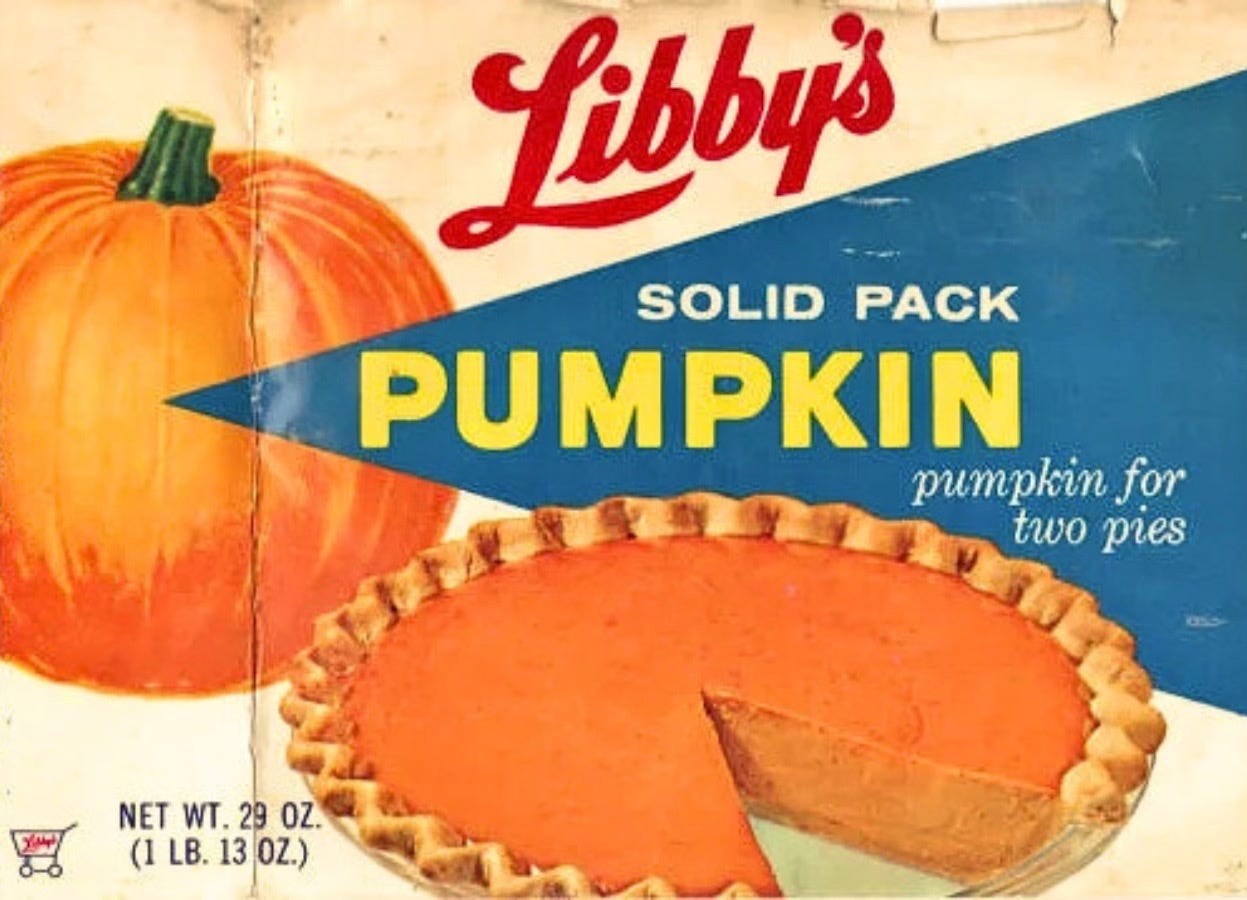

I had a whole thing planned for the conclusion of this column. I was going to write something about how pencil shavings and pumpkin pie like my mum used to make are about nostalgia, and the stuff imported from leafy, post-summer New England are about fauxstalgia, that melancholic joy for a place you haven’t experienced first-hand. I was going to write about how nostalgia and fauxstalgia offer the comfort of escapism from the coldest, darkest part of the year, a chance to roleplay at living in a world of cosy colours instead of the dismal, drizzling blue-grey that warns us winter is coming.

There’s probably something to that, but, honestly, I get tired of trying to find answers at the end of everything I write. I kill a lot of time reordering paragraphs and deleting-reinserting-redeleting words so I look productive while I try to find a ta-da! to end each essay with. I’m always looking for a thesis that explains, when really what I need is a theme to explore.

I went back to the start of Rumaan Alam’s article. I thought again about how he finds it tiresome “when people insist that the equinox is a more meaningful marker of time than the children going back to school”. There’s a lot in this of Bryson’s irritation with the pointy-headed know-it-all chucking aside first-person experience for universal absolutes.

In his essay, Bryson reminds us that even in science there are unknowns. It’s not that this leaves room for the subjective (I don’t want to argue for subjectivity of the gaps), but it moves us towards humility. And in humility, experience speaks more loudly because we stop assuming we’ve accounted for everything, that life can be tidied into neat categories. Instead, we let experience out of the box and tell it, Go ahead, sing your heart out.

So I’m not going to try to “solve” anything here, not this time. I’m going to throw my hands up and accept that autumn starts, for me, whenever I want it to start; I’m going to find most beautiful whatever place in the world I happen to find most beautiful; I’ll celebrate the season however the hell I want and you probably should too. And I’m trying to remember, as often as I can, to trade my certainty for awe.

Ta-da!