Notes on a Reading Life: What's Truth Got To Do With It?

“I don’t think the truth is some kind of polestar in the sky that we will one day get to. It’s more like an incessant striving.”

Take a look at this sentence:

“Writing future the king twilit on park Allosaurus mythology.”

I understand each of those words on their own. I know what “writing” means and “future” and so on. But I don’t get what they mean in relation to each other in this particular sequence.

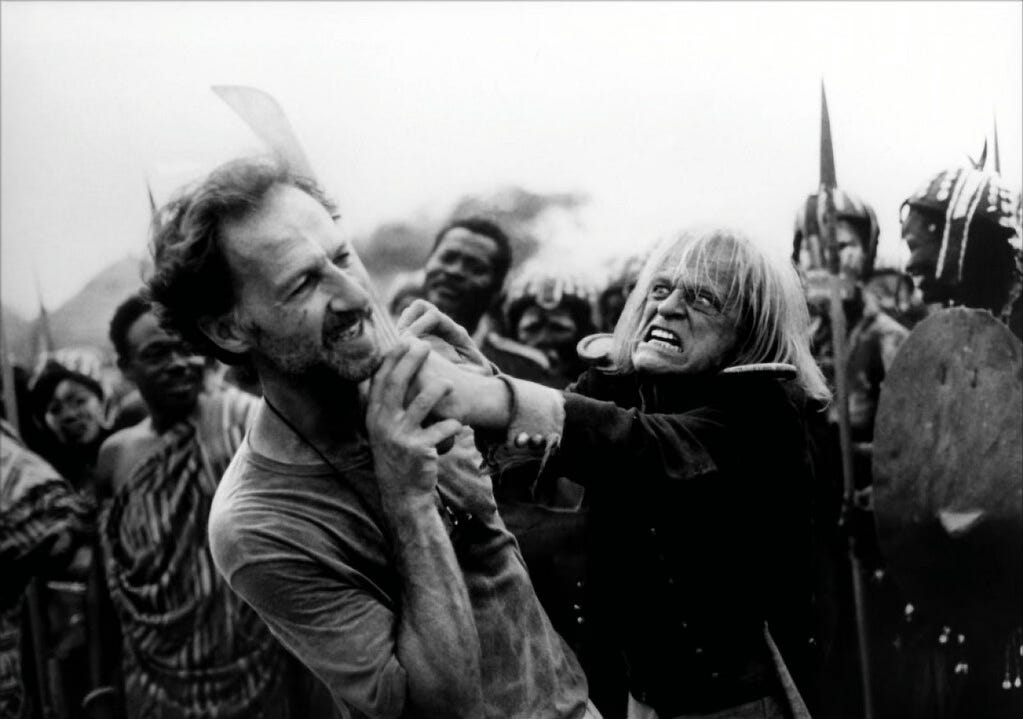

That’s how I felt when I started reading Werner Herzog’s new book, The Future of Truth. Each chapter and its paragraphs are intelligible in their own right, but I kept wondering what one had to do with another. I’d turn a page and think, How did we end up here?

How, for instance, did we get to this lengthy sermon on the impossibility of colonising Mars? And why are we now, a paragraph later, talking about AI systems learning to win at chess? And why is the page-long second chapter a description of how future intergalactic travellers will end up turning “pale and translucent, like outsized maggots”?

Back to the nonsense sentence above: someone could squint at the string of words and interpret (or interpolate) some meaning in it. Somebody else could suggest that I randomly plucked the words from books scattered around my desk. Others might say the sentence took form while I suffered a stroke. They’d all be arguing over what’s true about the sentence.

For the first few chapters of The Future of Truth, I obsessed over what the book means in that final, declarative sense so beloved by fundamentalists and the exhausted.1 Then I reconsidered Herzog’s claim on page one that truth is a journey, and I let myself relax into the flow of his prose, circle the eddies of his anecdotes, hoping the whole thing won’t just topple over the precipice of a terminating waterfall.

I should have said this at the top: I’m writing this in real time, having just finished chapter three. Stay tuned.

The Future of Truth is making me feel, on different pages, exhilarated and frustrated.

The exhilaration comes when I give myself over to Herzog’s decision to recount the entire plot of an opera, or write about a pig that gets stuck in a garbage chute and grows to take on “cubic form, wobbly as a great hunk of Jello”. Sure, I think, I’ll wander this way with you.

The frustration erupts when Herzog tries to get away with writing something like, “There is next to no difference between truth and the imitation of feelings” and moving breezily along. This is a remarkable claim for anyone to make, but to leave it unpacked in a book about the nature of truth is bizarre. Equally bizarre: the mid-paragraph leap from wishing poets were used as astronauts to some business section thoughts on Elon Musk as a corporate player.

Having passed the midpoint of this 110-page something, frustration has tipped the scale. I keep hoping for some deeper insight in what increasingly looks like a grab bag of Wikipedia entries chosen by someone with pinball attention. I’ve just read a series of barely connected anecdotes about Princess Diana’s death, actors hired to be family for the day, and Scott’s expedition to the Antarctic, ending with a hypothetical about the great explorer making pornography. What, I wonder, are we doing here?

It’s hard to escape the feeling of reading lists, especially when Herzog writes, “Let me list just a few here ...” and drops the names of some philosophers. Later, “I will list just a few ...” and we get a bunch of conspiracy theories. You look for something deeper than the list, something that turns it from mundane to meaningful, the difference between story and plot.2

There’s a whole chapter on crop circles and alien abductions that’s kind of interesting if you’ve never read about these things — but if, like me, you had a weird interest in the paranormal between the ages of nine and thirteen, or you have a friend who believes in aliens and talks about them after a few drinks, a page of this is more than enough.

Again, I want to know what Herzog’s going to do with these facts.

I think I get it, at last.

It’s not what I wanted — not that I’m owed anything by any writer — but it’s there: a discernible purpose, scrawled between the lines in lemon juice, and once you see it the book makes sense. It’s hinted at on the first page (before going largely ignored for the next seventy-five):

“I don’t think the truth is some kind of polestar in the sky that we will one day get to. It’s more like an incessant striving.”

Asked once what I think the meaning of life is, I said it’s to ask that very question. I said it in a glib tone of voice, and there’s something self-satisfied and artificially clever about it, but I also meant it sincerely. The truth — like meaning — isn’t a destination, it’s a direction.

This dichotomy sits between how I was reading The Future of Truth and how Herzog intends it to be read. The book isn’t an intellectual argument; it’s an experience to be had. It’s not leading the reader to a conclusion by way of evidence and syllogisms; we’re just going on a stroll. Like a new age guru with no time for new age gurus, Herzog wants us to look around and, like, be here in the moment, man.

I often keep two sets of books as a twenty-first century child of new atheism and someone who sees the world as a work of poetry. My most profound experiences come to me through metaphor and irony rather than facts and mathematics, but I still seek the affirmation of logic. Reading Herzog’s book with the heart instead of the head was a challenge. Still, whenever I demanded Herzog prove his point, or at least spell it out more clearly, I remembered this line from Christopher Hitchens:

“The literal mind is baffled by the ironic one, demanding explanations that only intensify the joke.”

The Future of Truth is definitely a joke, and like all the best jokes, it works because of the relationship between humour and the truth. Unlike comedy, however, there’s no clear punchline here. I’m pretty sure that’s what Herzog is giggling about.

“The concept of the ‘definitive text’ corresponds only to religion or exhaustion.” ~ The Homeric Versions, Jorge Luis Borges

“‘The king died and then the queen died’ is a story. ‘The king died, and then the queen died of grief’ is a plot. The time-sequence is preserved, but the sense of causality overshadows it.” ~ Aspects of the Novel, E. M. Forster