The Wood Between the Worlds

"Half-baked, barely functioning, eat-food-make-shit machines..."

I found out recently that someone I love is going through IVF. For them, for now, that means hospital appointments and hormones and waiting-praying-hoping. They’re living with desperate immediacy in every present moment, while I keep thinking in the future tense, looking forward to when a new baby will be in our lives.

It’s not only the IVF that’s got me thinking about kids. I’m thirty-eight and my wife just turned thirty-three, so babies are always in the next room over in our minds. We think we’ve shut the door to that room, but the catch is unreliable and the door keeps creaking open. I wish I could put a lock on the handle.

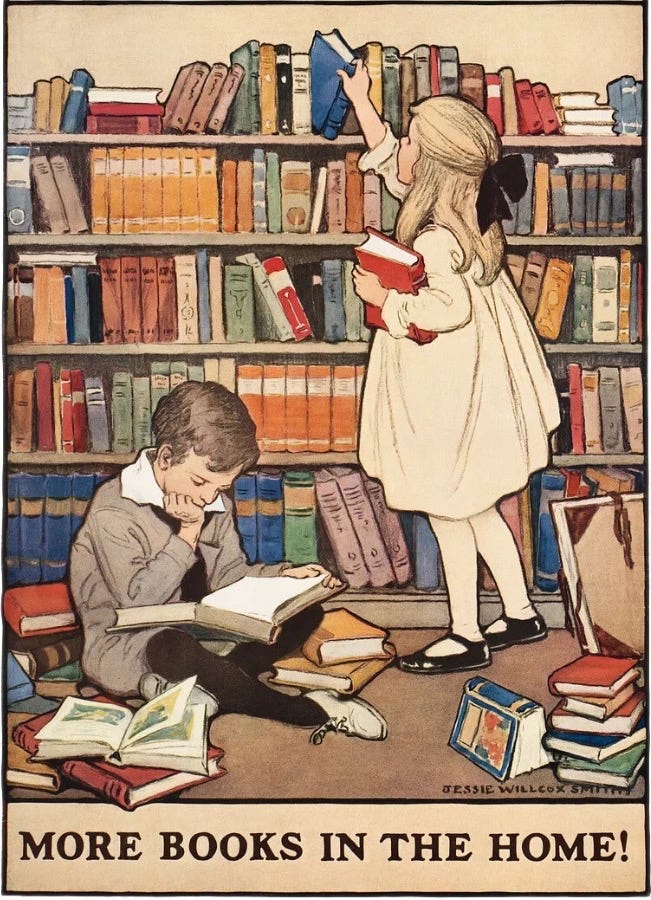

I love being an uncle though. My ever-growing troupe of nieces and nephews is made up of my siblings’ kids and the kids of my close friends. I keep a decent-sized collection of books that I loved when I was little so there’s always something for the niblings to read when they visit. I also keep that collection for nostalgia’s sake and the sake of comfort when grown-up life is too difficult to face head-on, but having all those nieces and nephews gives me an excuse.

So, I’m thinking about this new kid who might be joining us in the not-near-enough future. But it’s too soon to be thinking about a specific baby, with its own name and future personality and one-day taste in books, so I distract myself with thinking about babies as a concept and how strange they are.

Such as:

Humans are useless when we’re born. I think it has something to do with the fact that evolution gave us big brains that require big skulls, and the female pelvis isn’t built to push out a bowling-ball made of bone, so we have to be born before the skull gets too big. But that might not be true. It sounds like the kind of pop-science thing you learn as a kid and when you read about it as an adult, it turns out no one believes that anymore or maybe never did. Like that thing about bumblebees being too big to fly.

Whatever the reason, human babies are born early, before the loaf has fully risen. We come out as half-baked, doughy, barely functioning, eat-food-make-shit machines that are wholly dependent on others at the start of our lives.

One of the ways in which we’re underdeveloped is our vision. According to a book I found in my study and which I have no memory of buying, a newborn baby sees in black and white and only as far as eight inches from their face. After six weeks, that expands to about ten inches. That distance keeps growing over the following months. That means the whole world for a baby is about eight inches around, at first.

A baby’s world is also remarkably unpopulated. There’s only one person in existence; other people (a non-concept for the baby) are just animate objects that bring soothing sounds and food. Basically, in the beginning, we depend entirely on other people for our survival and are incapable of even knowing they exist.

Like I said, we’re useless when we’re born.

Eventually, the baby perceives the divide that brings “I” and “you” into the picture. They’re introduced to someone called “self” and someone else called “other”. The visible world expands, and the invisible inner lives of all these other people multiply, and it becomes clear that there’s more to reality than first-person experience. The universe has suddenly become a multiverse. The next step is working out how to move through these worlds.

In The Magician’s Nephew (chronologically the first in the Narnia series by C. S. Lewis), the rules for moving between worlds is laid out with the fuss-free clarity of children’s fantasy. There’s two kinds of ring, a yellow ring and a green one. If you touch a yellow ring, you vanish from our world and wind up in a strange forest full of pools. You put on a green ring and jump into one of these pools and the water takes you to one of many fantastical lands.

This realm that joins one world to all others is called “The Wood between the Worlds”. The wood is a little like this growing awareness infants have of all the possible worlds people could inhabit, at least in their imaginations. The pools of water, then, are books. Or maybe the rings are books. Either way, books transport us to those other minds and the worlds that exist in them.

Here’s my first memory of reading:

I’d guess I’m about five years old; my family is living in a small city in the Canadian mountains; I’m on the kitchen floor early in the morning — the memory is washed in dim blue light — and I’m putting together the letters of a newspaper headline. When I read it out loud and understand the words, I run into my parents’ room to wake them up and announce the achievement. I’ve discovered the Wood between the Worlds.

Part of my private mythology about myself as a reader was that reading a headline at that age made me terribly precocious. That myth went the way of dragons and a flat Earth when I grew up and discovered that my feat of intellect fell well within the normal range of childhood development.

But that didn’t bruise my self-belief as much as reading about Roald Dahl’s eponymous Matilda, who discovered reading, the public library, and that Charles Dickens could make her laugh, all by the age of “four years and three months”. When she and I first met, I was twice her age and had read half as much, certainly none of the grown-up titles in the literature she’d read before the end of the first chapter.1

Still, the pin-prick to the balloon of my ego was offset by the joy of being transported into Dahl’s world, Matilda’s universe, and discovering I wasn’t the only one who knew about the Wood between the Worlds. Dahl tells us what the books Matilda borrowed from the library did for the “sensitive and brilliant” little girl:

“The books transported her into new worlds and introduced her to amazing people who lived exciting lives. She went on olden-day sailing ships with Joseph Conrad. She went to Africa with Ernest Hemingway and to India with Rudyard Kipling. She travelled all over the world while sitting in her little room in an English village.”

Matilda had her travelling companions, and she became one of mine.

People like me (book botherers, professional readers, page pushers, call us what you will) like to say grandiose things about what books are and what they do. It’s probably a side effect of living so intimately with language — all the noisiest words that clamour for attention have a tendency to come out when we’re really passionate about something. I know it, I own it, and I stand by the next paragraph without shame:

For the imagined kid whose progress we’re tracking here, learning to read isn’t only a matter of a skill attained, not just a qualification or a tick in a box for child development — it’s an infinite library of new worlds to explore and a guide to exploring them. It’s both the territory and the map.

For the imaginary Matilda, reading expands her world, which would otherwise be as small as it is for her parents. Their brains are trapped in the TV set they stare at, while her mind roams free in her books. “All the reading she had done had given her a view of life that they had never seen.”

There’s another imagined child, the one I’ve been trying not to imagine this whole time, the one that might be joining us soon if the gods of medicine smile on the IVF. I will allow myself this much thinking about that possible future and no more: I really can’t wait for that kid to discover reading.

NICHOLAS NICKLEBY by Charles Dickens

OLIVER TWIST by Charles Dickens

JANE EYRE by Charlotte Brontë

PRIDE AND PREJUDICE by Jane Austen

TESS OF THE D’URBERVILLES by Thomas Hardy

GONE TO EARTH by Mary Webb

KIM by Rudyard Kipling

THE INVISIBLE MAN by H. G. Wells

THE OLD MAN AND THE SEA by Ernest Hemingway

THE SOUND AND THE FURY by William Faulkner

THE GRAPES OF WRATH by John Steinbeck

THE GOOD COMPANIONS by J. B. Priestley

BRIGHTON ROCK by Graham Greene

ANIMAL FARM by George Orwell

Lovely reflection, Matthew. I pray your loved ones have success! They are blessed to have such a thoughtful friend/uncle!

I forgot how much I loved Matilda until just now, even though I read it probably thirty years ago when I was around your age of discovery (7-8ish). As someone who actually sort of teaches kids reading, I think the Narnia reference might be the most powerful one, though: kids need to read so many series books before they can be properly challenged by a big, difficult book. Kids like Matildas or Ludo in Helen DeWitt’s The Last Samurai, aren’t really the model for lifetime reading or even getting good at reading fast. Instead, the most likely reason I could understand Steinbeck and Dickens and Conrad in late elementary/ early middle school was because they reminded me of Dahl, Lewis, Leguin, and hundreds of trashy sci-fi, mystery and fantasy series novels (Goosebumps, the Hardy Boys, Animorphs, etc.) A plot has to be muscle memory before a reader can understand when an author is subverting it, or just telling a standard plot but with extremely challenging but satisfyingly beautiful language. Anyway, I’ve got my own kids and nieces and nephews that I’m excited to see through this journey, and I appreciate this post.