Lost in the Library

I plan therefore I am.

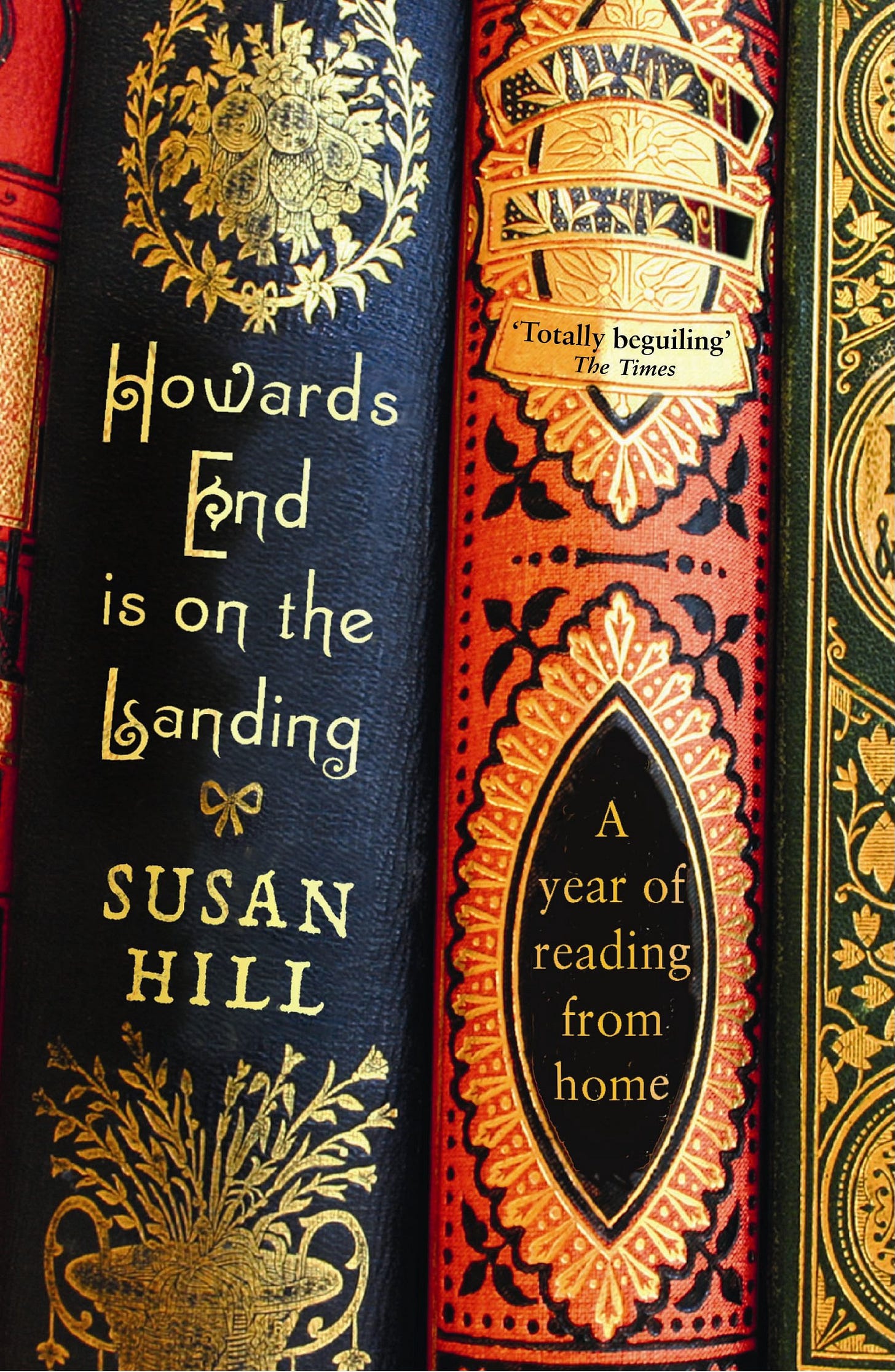

It begins like this. Susan Hill goes searching for a book she’s lost among the shelves and bookcases filling her country home. Every room the novelist enters reveals “a dozen, perhaps two dozen, perhaps two hundred [books] that I had never read”. Then she notices all the books she’s read and forgotten. Then the ones she remembers and wants to read again.

This leads to Howards End is on the Landing, an account of Hill’s plan to spend a year re-reading her home library. She wants to get to know these books again and, by extension, get to know herself. Re-reading a book can be like meeting up with an ex because you want to remember who you used to be, so you can affirm the person you’ve become. Like an ex, the book has seen you naked, argued with you, and shaped a bit of who you are.

Hill puts it like this:

“If you cut me open, you will find volume after volume, page after page, the contents of every [book] I have ever read, somehow transmuted and transformed into me. Alice in Wonderland. The Magic Faraway Tree. The Hound of the Baskervilles. The Book of Job. Bleak House. Wuthering Heights. The Complete Poems of W. H. Auden. The Tale of Mr Toad. Howards End. What a strange person I must be.”

Howards End is on the Landing became part of who I am back when I was an adult but not yet a grown-up. In some immeasurable yet deeply felt way, it altered how I read — but I can’t remember a word of it today. I don’t like my unreliable mental record of things that matter. Hill has a bit about this too:

“Memory is like a long, dark street, illuminated at intervals in a light so bright that it shows up every detail. And then one plunges into the dark stretch again.”

The dark stretch scares me. Sleep is sometimes compared to death, but the darkness and absence of forgetting is far worse because you’re aware of it. You know there’s something you don’t know that you used to know. Unlike death, however, forgetting can be reversed.

In December, on the darkest day of the year, I go to a bookshop and buy a second-hand copy of Howards End is on the Landing to remember what I’ve forgotten. This is how the dark stretch of winter is lit up: by reading and remembering.

I pass the finish line of December (soft sigh, body sags) and then (deep breath, shoulders back) greet January with a list for self-improvement. My New Year’s resolutions are like advisories on an MOT — you passed the test, but only just, and we recommend you fix the following so you don’t fail next year.

My resolutions always orbit books. There’s exercise and food, sure, and it’s become a mark of pride to insist on learning how to dance and reaching the end of the year without learning how to dance. But mostly it’s resolutions about how much I read, and the kind of thing I read, and new ways of structuring that reading.

Last year, I announced in these digital pages that I intended to read more books from before the twentieth century. The best-laid schemes o’ mice an’ men... I planned to read Silas Marner, and it sits on the shelf unread, casting judgmental looks my way. I’d meant to finish Jane Austen’s complete works, yet they remain unfinished. I’d really wanted to read Middlemarch, honestly I did, but... You get where I’m going.

Most of the books I wrote about last year were published in the twentieth century. There was A Single Man and The Bell Jar and The Haunting of Hill House and The Ghost Writer and a bunch of others. I needed no incentive to read them again. Failing my resolution resolved the fact that I am, in my soul, a twentieth century reader. This brought some blurry outlines into focus, revealing with sharper clarity what I’m doing here at Volumes.

So there’s value to these resolutions even as I fail them, because a) they keep my reading intentional — I read more of the classics than I would have without that resolution — and b) I win whether the coin comes up heads or tails. I stick to the resolution and succeed, or I fail and learn something about myself.

Besides, I’m more optimistic about my abilities than my tally of past success and failure should allow. I’ll hear about someone’s reading plan and, leaning close like a customer suckered in by a sales pitch, I’ll think, Huh. I could do that.

As I re-read Howards End is on the Landing, I consider Susan Hill’s project of re-reading for a whole year. I lean in close and think, Huh. I could do that.

There’s a story about the not-so-well-known historian David Herbert Donald hosting a party at his home for the far-better-known Gore Vidal. Looking over the stacks of books in every room of the house, Vidal asks his host how many books he owns. Donald shrugs and says, “About 12,000.” Vidal, somewhat surprisingly for a man of letters, asks the question non-readers ask when they enter a reader’s home and see all the books: “Have you read them all?” Another shrug and Donald says, “No, but I know what’s in them.”

Could I say the same? How well do I know what’s in the books I own? As Bilbo Baggins said (sort of), I don’t know half of them half as well as I should like. I don’t know the full work of any author the way Susan Hill knows, say, the books of Dickens. There’s a bit in Howards End is on the Landing where Hill talks about her relationship with Dickens and she says:

“His flaws are huge but magnificent — and all of a piece with the whole. A perfect, flawless Dickens would somehow be a shrunken, impoverished one.”

It’s a generous thing to say and an intimate thing to know about a writer. For knowledge like this, you have to read all of a writer’s books (the minor as well as major works) and you have to read them, in Hill’s phrase, “well, widely, and deeply”. This means re-reading.

Reading a book once is like spending an evening making nice at a cocktail party where you meet each guest and find out their name, job, married, kids — the surface stuff that makes an acquaintance but not a friend. For friendship you’ve got to go deeper. You need to be able to see the full sweep of the artistic vision, by placing each book in some kind of context. That means getting to know its neighbours, its friends, its rivals.

It means getting to know a library.

Working horizontally beneath a blanket, instead of upright at my desk, is a half-holiday when I’m not feeling great, so today I’ve been writing from a makeshift bed on the sofa. Now, though, I get up and wander around my apartment, examining the books lined up and stacked and scattered around various rooms. Picking up a heavy hardback with a hessian-textured cover, I wonder how it relates to the books further along the same shelf, books by other writers working in different eras and genres.

They have the alphabet in common, sure, and that’s how Philip Roth ends up at Sylvia Plath’s table with Muriel Spark a few seats over. They’re also together because they fit some scheme by which I’ve organised my books. I wonder if that reveals something — about the books, about me, about anything. I think it’s the particular sequence of books in our own libraries, the ways they interact and catalyse each other, that makes up our literary DNA.

“Literary DNA” isn’t my phrase, it’s Susan Hill’s, and its flirty little appearance in my mind makes me realise that I overlooked a key part of that quote I copied out above, where Hill says that books are a part of who she is:

“But if the books I have read have helped to form me, then probably nobody else who ever lived has read exactly the same books, all the same books and only the same books as me. So just as my genes and the soul within me make me uniquely me, so I am the unique sum of the books I have read. I am my literary DNA.”

Still wandering from room to room, I casually catalogue the novels, poetry collections, short story anthologies, comic books, and non-fiction on the shelves, bookcases, counters, ledges, and tables in my home. This is my literary DNA.

That should be the challenge for this year — to get to know my library again. To lose myself in the wood of books that’s grown around me over so many years, and to rediscover who and where I’ve been, what I’ve done and believed, with an eye on where it might lead me.

This is my modest though meaningful resolution for the year: to read and remember.

What a wonderful article. As I get older I too have had some issues with retaining the books that I read, and it can be frustrating and alarming. I went through a stage where I would reread many of my books as much for comfort is anything. You remind me a little bit of myself when you mentioned casually perusing your bookshelves for any kind of structure or order to them. The last year or so I've been making a conscious effort to build my physical library and I've been amassing books that I've loved growing up, books I plan on reading in the future, and even ones that I just found interesting in the moment. Right now they're shelved half hazardly. You might find My collection of Nathaniel Hawthorne sitting next to the complete works of Ambrose Bierce. Or Orlando Furioso next to Westward Ho. Each literary work is a piece of my DNA, like you mentioned. Each has contributed to the sum of my parts. It's good to know there are others that have perceived this in a similar way.

Fascinating! I've particularly enjoyed re-reading classics like Frankenstein and 1984 (which was depressingly relatable) recently because I gleaned so much more from the lines that didn't resonate with me as much upon first reading them.