Myth and Memory

Getting happy-sad at the sound of a dial-up modem.

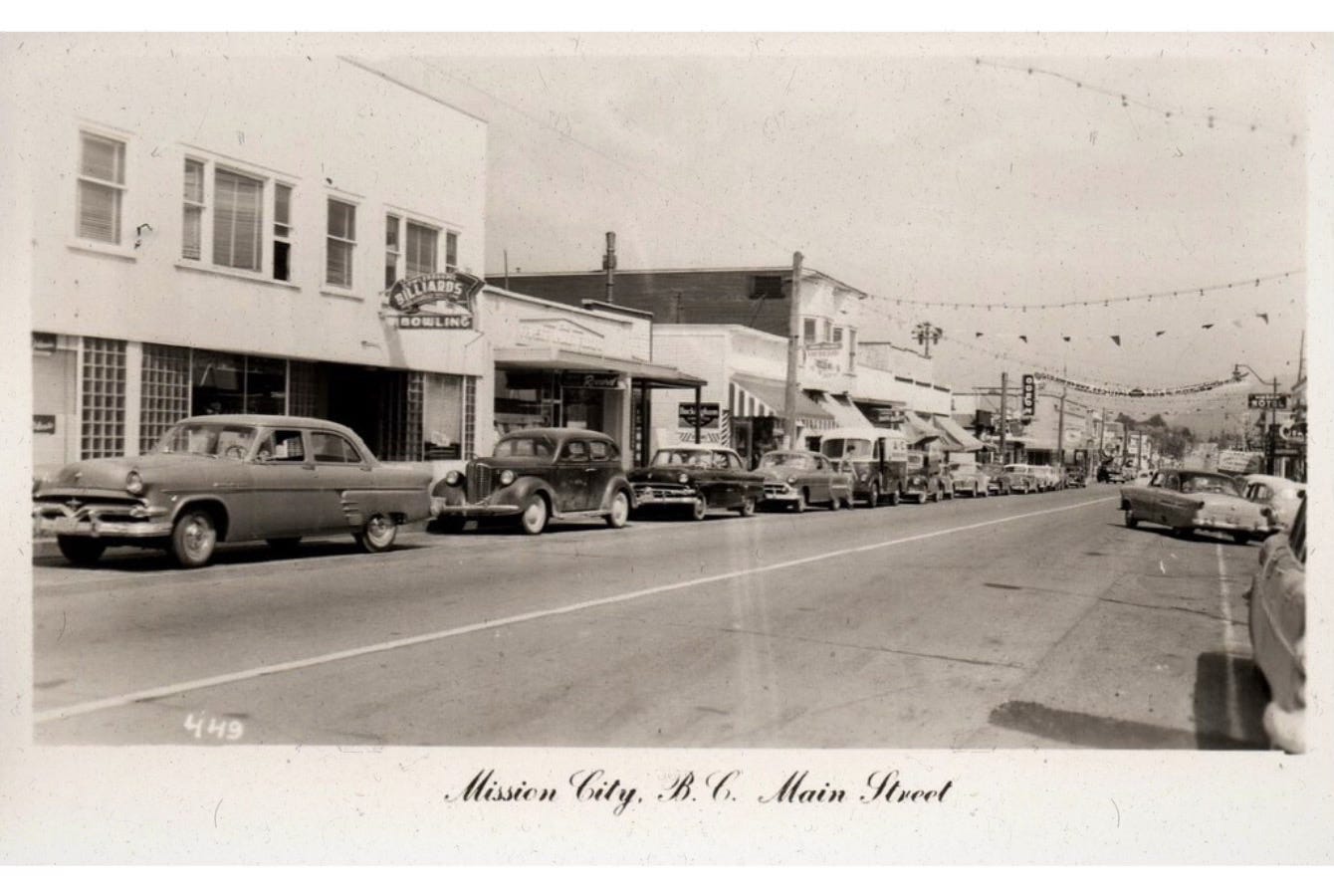

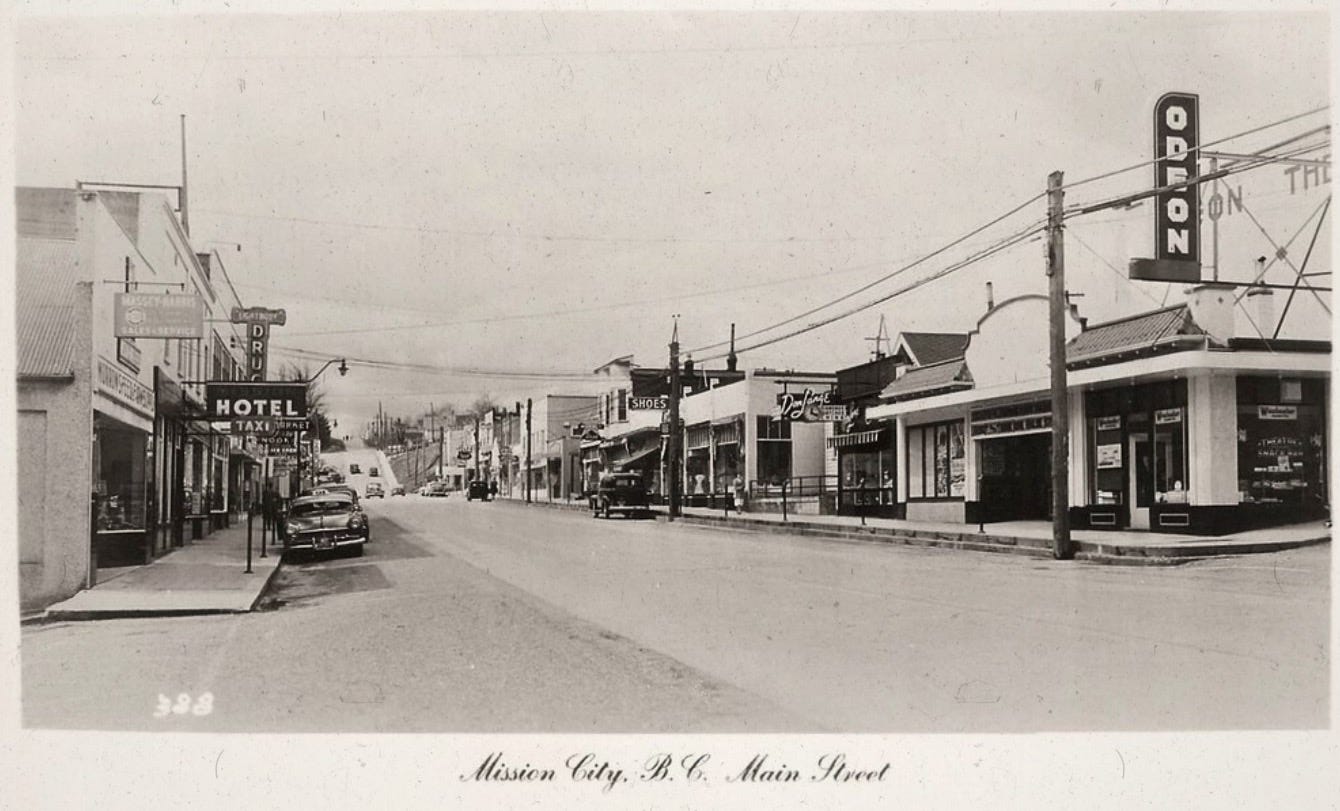

I grew up in the mountains of British Columbia, in a town called Mission, a place that reminds me of Bill Bryson’s line about his own origins: “I come from Des Moines. Somebody had to.” I’m not the only person to come from Mission; the singer Carly Rae Jepson is from there. Mission is also where some of a show called Riverdale was filmed. I’ve only just about heard of the singer or the show, but this is fame of a kind.

When I look up Mission on that site you’re not supposed to trust for information (rhymes with “schmicky-schmedia”), I find out that my hometown is, in fact, a city. Either it grew in my absence or it seemed smaller and pokier when I was little. Kids are solipsists, and I was no different: Mission existed only as far as I explored it, like a video game rendering the world only when you move your character to that part of the map.

When you’re doggy paddling in the choppy waters of memory, objectivity feels like a branch to cling to, so I google again: Mission was reclassified as a city in 2021, a quarter century since I left. I guess the place had ambitions I was unaware of. But facts like that don’t move me; I’m interested in how I remember my hometown, correctly or not.

Mission was the kind of place where your mum might tell you to look out the window to see a grizzly bear sniffing around your garbage cans, or you’d get up to pee in the night and hear the haunting, haunted howl of a coyote. In Mission, the urban abruptly gave way to the wild. You’d be walking through a car park and cut through a gap in a bush and there you’d be in the inarguable wilderness — forests that felt like they went back to the time that all stories are once upon, with trees that reached so high and wide you were sure they’d outlast us all.

My dad and I went hiking on a wet Saturday morning. I was maybe eight years old, and I was wearing one of those raincoats that keep out the water but not the cold, and I hadn’t put the hood up like my dad told me to, so the rain was running under my collar and down my back. The earth writhed with water and worms. I almost stepped on a juicy, yellow banana slug. I can still smell the skunk cabbage at the edge of the deer trail we were following, a weed with one of those awful pongs you feel compelled to sniff twice. We were on an adventure.

Then my dad said something unexpected and magical. He told me, over his shoulder, like it was no big thing: “We’re going to have to climb across a cliff face.”

The remembering me knows this wasn’t as dangerous as it sounds — I was a kid, we weren’t free soloing — and we were only going to pass over a path many hikers followed across the top of a stony slope. My dad probably phrased it the way he did to get me excited. It worked. What he wouldn’t have anticipated is how spectacularly I misunderstood what he meant.

I followed my dad deeper into the forest believing I was going to see a hidden wonder of British Columbia: Canada’s version of Mount Rushmore. When my dad said something about us having to go over the lip of the rock face, I imagined us shuffling, side by side, along the mouth of whatever face was carved into the exposed mountainside. We’d be rugged explorers seeking handholds in each nostril as we travelled from one cheek to the other.

Frustratingly, and in violation of the desire for narrative closure, I have no memory of actually reaching the cliff, nor my reaction to the reality. I can’t picture a thing about the real rock face — but nor do I remember any disappointment. What I do remember is the fantasy, the unrestrained belief and largeness of what I’d imagined. I remember it in a single image: an absurdly large face that never existed, carved into a cliff I’ve otherwise forgotten.

In her memoir, Penelope Lively notices that “childhood memories have a high visual content”. It’s true that what I remember most clearly is what I can see most clearly. There are no passages of memory where audio plays over a black screen with footage not found stamped on it. The things I recall are always anchored to an image.

Sometimes the memory is a video, sometimes it’s a snapshot that shimmers and shakes. I used to have a picture that came with Michael Crichton’s The Lost World, a 3D image of the Jurassic Park logo, and turning it side to side made the T-rex smash through the picture in a stop-motion movement of limited range. That’s what these snapshots of memory are like.

These images are tricky things. Their memories seem more reliable because I can “see” them, like the swing I flipped off of backwards, accidentally, while the flesh of my middle finger was trapped in the links of the chain and the skin tore as I fell, leaving the V-shaped scar I’m looking at now, thirty years later. The scar proves it happened, and the picture in my head shows a red swing, so that proves it was red. But if I tell myself to picture it green, I’m just as sure it was green. The inner testimony of the courtroom sketch artist in my head is unreliable.

Still, much of it can be trusted. Lively writes about returning to Egypt after decades away and finding “that words and phrases of Arabic came swimming up, that I must once have known and had not forgotten but had put away somewhere”. I only lived in Mexico for half a year, so my Spanish was weak and has since abandoned my conscious mind — but, as Lively puts it, “the ghost of it is there in my head.” Sometimes strangers talk Spanish to me in my dreams, and I respond with a breezy, “¿Cómo puedo ayudarte?” The stranger and I shoot the bilingual shit, and when I double check in the morning, I find I was making perfect sense. It turns out I remember things that I can’t remember.

I wonder what other memories have settled beneath the sediment of my subconsciousness. That’s one reason I keep mementos scattered around my daily life, anchors to things I’m scared to forget. This is tangled up in a ton of nostalgia. Like everyone who was a kid in the nineties, I get happy-sad at the sound of a dial-up modem. The absence of smartphones in old movies feels like a temporary, vicarious detox. And there’s something reassuringly simple about a ring binder stuffed with papers, or a finger-staining newspaper folded under the arm, or a heavy encyclopaedia that cracks when you open it to look up some necessary fact.

But the way I choose to remember this past isn’t how things really were. I look back at analogue life as a wonder, as if the kid I used to be was blissfully complete with his lack of digital marvels. Back then, however, I looked forward to the MP3 players, social media, and video on demand that I didn’t even know were coming. In recreating those days in memory, I forget how bored I was while I was living them.

To tell the story I want to tell out of my memories, I have to trim back scenes here, shuffle chronology there, squash context to make today’s values fit yesterday’s social constructs. It’s what the author Daniel Kraus once called creative taxidermy, and it’s why the poet Joanna Kyger said, “Myth is the practice of memory.”

I don’t worry that I can’t picture the precise path my dad and I followed to the cliff, or the details of the actual rock. I’m just glad I know he and I went on that hike, and that I remember the face that was never there.