A Reader's First Love

“Few things leave a deeper mark on the reader than the first book that finds its way into his heart.”

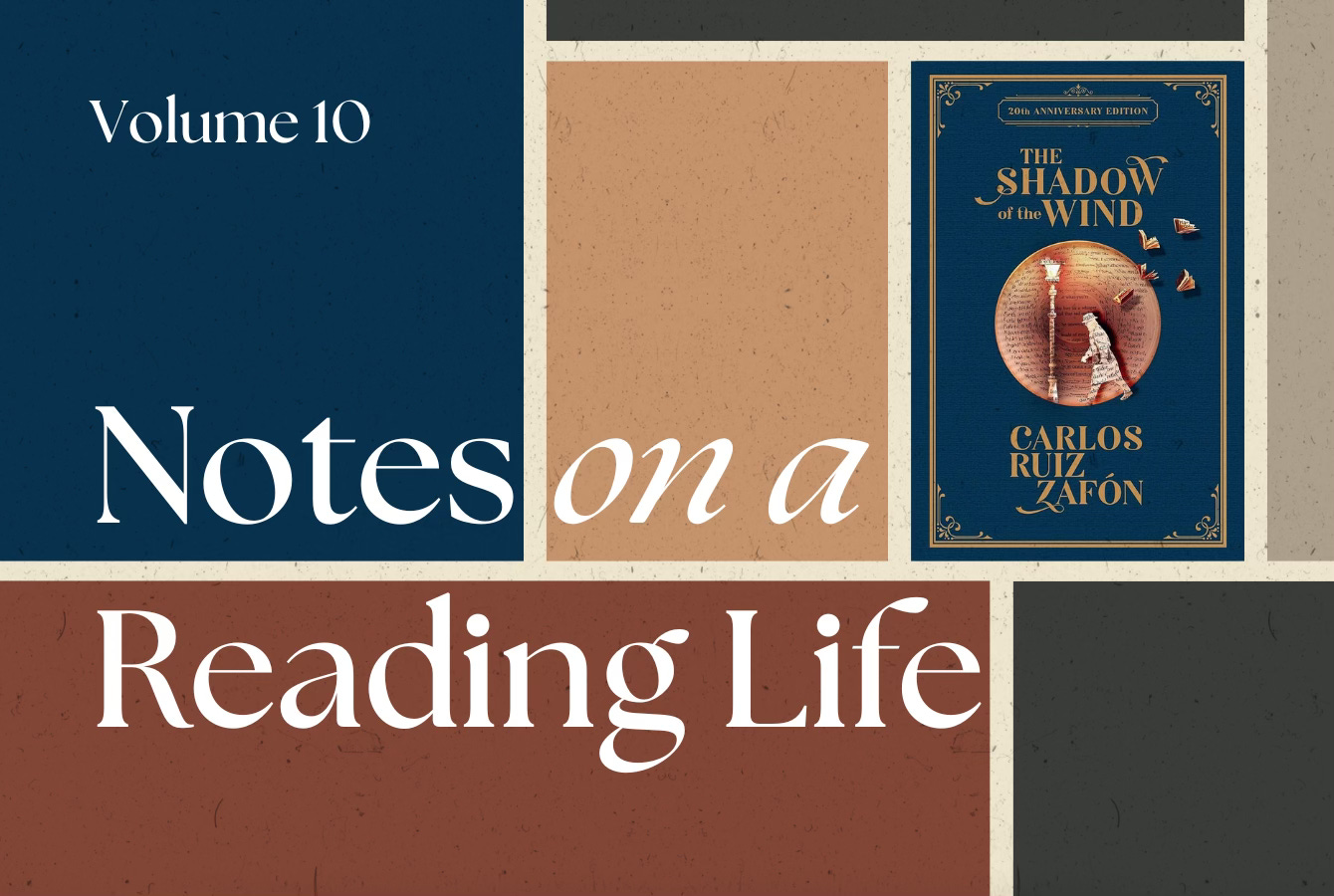

If I were a superhero (writing faster than a speeding bullet, with similes more powerful than a locomotive, able to read big books in a single sitting) my origin story would include at least these two novels: The Shadow of the Wind by Carlos Ruiz Zafón, which I first read twenty years ago in my late teens, and The Ghost Writer by Philip Roth, which I first read in my early-twenties (and which I wrote about last week).

The Ghost Writer shaped how I thought of myself as a writer. The Shadow of the Wind changed my identity as a reader.

The Shadow of the Wind was my first book about books, the kind filled with wonderfully grand statements that inevitably end up copied into notebooks and social media. One of the many quotable lines in The Shadow of the Wind is reproduced on the back cover, axiomatic enough to serve as a blurb for any good bibliophile:

“Few things leave a deeper mark on the reader than the first book that finds its way into his heart.”

True enough, and part of the reason I returned to both books last month.

In The Shadow of the Wind, a young woman waxes unashamedly poetic about the first book that took seed in her heart:

“I had never known the pleasure of reading, of exploring the recess of the soul, of letting myself be carried away by imagination, beauty, and the mystery of fiction and language. For me, all those things were born with that novel. […] That book taught me that by reading, I could live more intensely.”

Of course I loved reading that paragraph. This is my whole thing with Volumes — learning to live the good life, or at least a better one, through reading. Building a life out of books. I’m not immune to confirmation bias; it’s one of my favourite biases. So if a book does some of the aggrandising I normally have to do myself, if it applauds what I spend my time doing, and if it happens to have a fun literary-thriller story to go with it like The Shadow of the Wind has, I’m in.

I just have to ignore that nagging feeling I get when I’m in agreeable company that warns me I’m probably missing something, some important critique through which I might grow if I could hear it, the kind of the thing a supportive friend (or book) might not tell me but a critic will.

If The Shadow of the Wind is a celebration of readers and reading, The Ghost Writer celebrates writers and their frequently weird ways of seeing the world and living in it. Or — as is the case for Lonoff, the great-writer character in Roth’s novel — not living in it.

If the young woman in Zafón’s book learns “that by reading, I could live more intensely”, Lonoff in Roth’s novel has learned that by ignoring life, he can write more intensely. He barely goes out of his house, rarely has any guests, and he expects silence and stillness from his wife, just as he’d demanded of his children before they grew up and escaped the stifling boredom of his existence.

So how (I wondered as I re-read The Ghost Writer) does Lonoff have anything to write about? From what raw ingredients does he bake his books? There are two hints at how he achieves success in the novel:

He insists on questioning the narrator about his “unhallowed life” of day jobs and girlfriends outside of his writing career. No doubt Lonoff is storing away these accounts of real-world drudgery for future retelling as stories on the page.

The narrator discovers that Lonoff has extensively underlined some articles in a magazine, and if you collected just the noted sentences together you’d have “a perfect precis of each piece and would have served a schoolchild as excellent preparation for a report to his current-events class.”

Lonoff is learning the world like a student — from books and research, rather than from living.

There’s an essay I read a few years back called “Theology and Self-Awareness”. It’s by a theologian called H. A Williams, who writes:

“[There] are no supersonic flights to the Celestial City or even the Palace Beautiful. Increased awareness can be obtained only by a journey on foot by way of the Slough of Despond, the Hill of Difficulty, Doubting Castle, and the rest.”

He goes on later to blow wet, insulting raspberries at the wound already dealt to my pride as someone whose work life is made up of his reading life which in turn forms most of his daily life:

“There is a type of thinking which remains safely at home, merely receiving reports, maps, and photographs of what lies beyond the garden wall, and speculates, often with great cleverness, on the basis of such dispatches received. Thinking and living are thus divorced, or rather, thinking is made into the instrument of escape from involvement with life.”

Fine, it’s possible to take the whole “reading life” thing too far, or to let it take you in an unhealthy direction, to a life less abundant. Of course, the extremes of things are rarely their best manifestations. How, then, to read like the woman in The Shadow of the Wind, who learns that with books she can “live more intensely”?

She (why haven’t I named her yet? She’s called Clara) is blind. When she and Daniel, the narrator, walk through their neighbourhood in Barcelona, she asks him “to describe the façades, the people, the cars, the shops, the lampposts and shop windows that we passed on our way”.

Taking in his words to form mental images, she’s able to see both the Barcelona her eyes can do nothing with and, as Daniel says, “our own private Barcelona, one that only she and I could see”.

Clara says something else about the first book she loved: “It could give me back the sight I had lost.” The world comes to her, in part, through books. Stories, whether read in silence or heard out loud, grant access to the real world and to imagined ones.

Last year, my younger sister got married, and though I tried to be “present” as the lingo has it, I kept filtering it through language. I got home and wrote about what happened that day. One of the things I wrote is useful here, because it gives us a decent metaphor for the relationship between books and the world:

“Maps, as the saying goes, are not the territory — but maps are still instructive about the nature of the territory. They can be useful guides to the terrain.”

Books are maps that guide us through the world they describe (even when they describe unreal worlds). The point is to find the world through our reading, to access it in new and useful and vibrant ways. Or, if books aren’t maps, they’re keys that unlock doors that lead to life out there.

It’s not that you need fewer books in your life, just more of the other stuff to go with it. You can write about writing, and you can read about reading, and life itself is for living. I think I read that somewhere.